Where Patient and Provider Wellbeing Intersect: Narrative Medicine Enhances Ultrasound Procedure Training for Medical Students

Imagine on your first day as a medical intern, you are tasked with performing an ultrasound-guided procedure. You are confident in your knowledge gained from four years of medical school, but there are still the questions of how to adapt the procedure to the current patient’s anatomy, how to discuss the procedure and its risks with the patient, and what to do if something unexpected happens. This is the very scenario an elective for fourth-year medical students at UCSF School of Medicine is designed to address. Hands-on experience combined with narrative medicine principles in a structured setting offers a holistic approach to scenarios that newly minted doctors might encounter before, during, and after a procedure.

Miles Conrad, MD, MPH, designed this ultrasound procedure elective in 2022 and envisioned a training experience that transcended hands-on technical skills. Preethi Raghu, MD, who co-leads the session with Conrad, brings her experience with narrative medicine to help trainees both handle and communicate the unexpected. "We wanted to create well-rounded physicians," explained Raghu, "Individuals who know how to perform procedures well while navigating the emotional complexities that come with them, particularly when there are complications." The annual elective ultrasound procedure course has about 20 students each year, all graduating medical students who will soon be performing procedures as interns.

This year, the students were assigned pre-session work, an episode of The Nocturnists podcast hosted by Emily Silverman, MD, titled See one, do one, teach one. The podcast shared one interventional radiologist’s experience of a complication in the middle of a procedure and the harrowing process to fix it. Instructors then engaged with trainees using questions such as, “Have you seen a near miss or a medical error?” Speaking frankly about medical errors can be traumatic. For medical professionals, these incidents can elicit instinctive reluctance, feelings of inadequacy, and shame at possibly causing harm to patients.

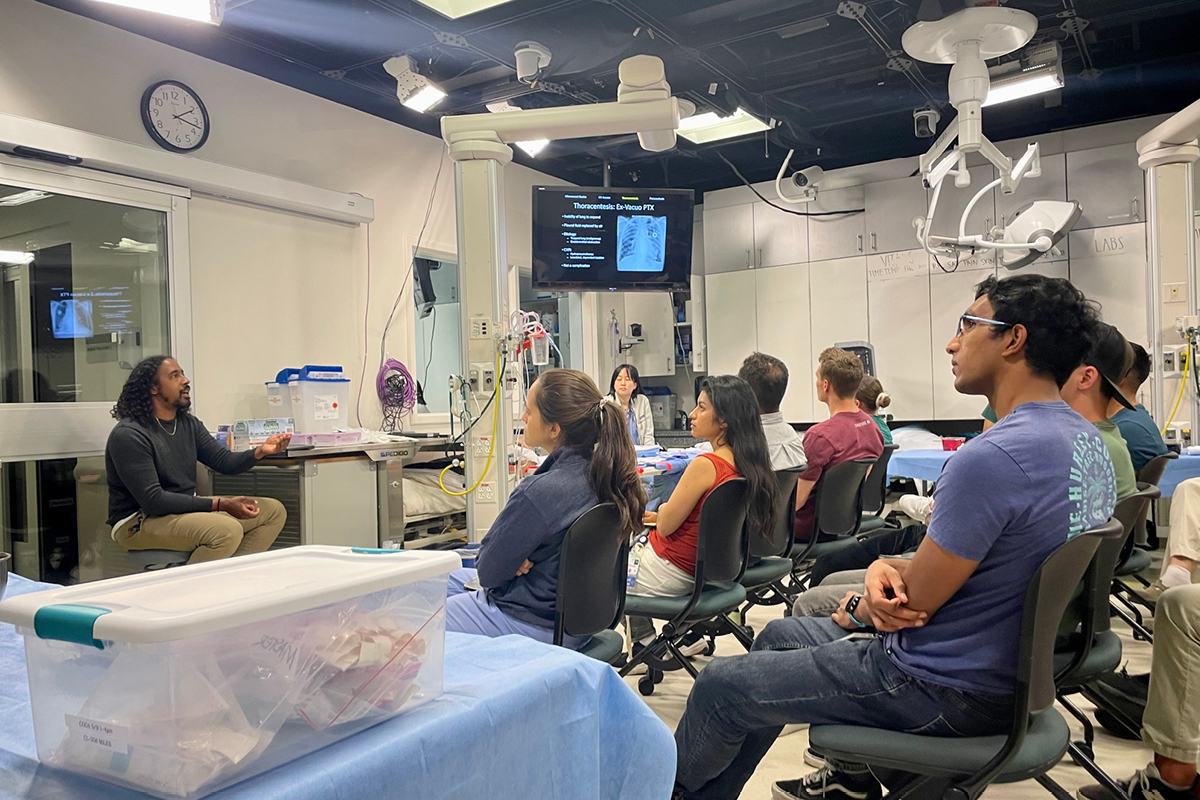

This year, the students were assigned pre-session work, an episode of The Nocturnists podcast hosted by Emily Silverman, MD, titled See one, do one, teach one. The podcast shared one interventional radiologist’s experience of a complication in the middle of a procedure and the harrowing process to fix it. Instructors then engaged with trainees using questions such as, “Have you seen a near miss or a medical error?” Speaking frankly about medical errors can be traumatic. For medical professionals, these incidents can elicit instinctive reluctance, feelings of inadequacy, and shame at possibly causing harm to patients. The first hour was led by Dr. Conrad and Christopher Brunson, MD and focused on didactic lectures, exploring the step-by-step process of performing procedures and highlighting potential problem areas in procedural techniques. Students are guided through the procedures and provided with valuable insights shared from the instructors’ own experiences with complications. This session emphasizes patient safety by explaining potential complications through the lens of personal experience; what they tried, what went wrong, and how they fixed it.

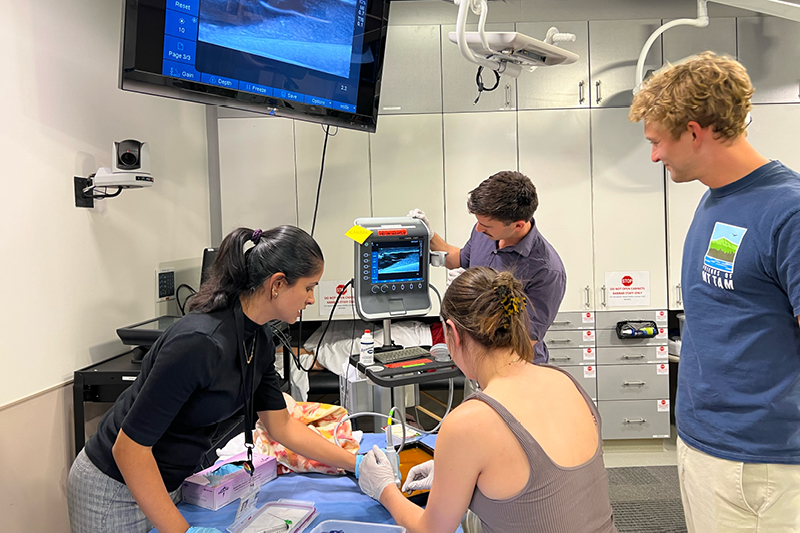

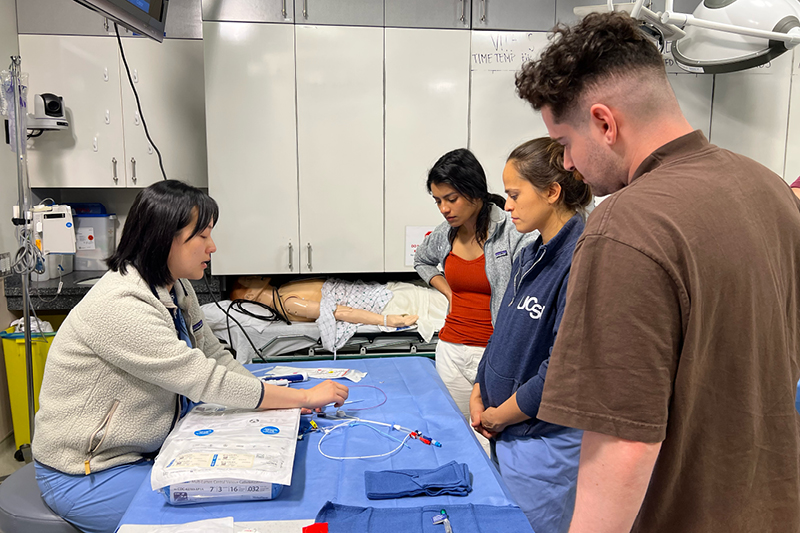

The second hour of the course offers a hands-on interactive component, where students rotate through different stations, practicing on simulated materials and phantom patients. By placing needles or lines into blocks of gelatin and tofu, students gain valuable experience, familiarity, and muscle memory before applying their skills to real patients. Xiao Wu, MD, helped the students with the simulations, drawing on her experience as a resident pursuing interventional radiology. The elective covers procedures such as thoracentesis, paracentesis, vascular access, biopsy of a superficial target lesion, and aspirating cysts/collections. Trainees also familiarize themselves with catheters, needles, and other common equipment.

The second hour of the course offers a hands-on interactive component, where students rotate through different stations, practicing on simulated materials and phantom patients. By placing needles or lines into blocks of gelatin and tofu, students gain valuable experience, familiarity, and muscle memory before applying their skills to real patients. Xiao Wu, MD, helped the students with the simulations, drawing on her experience as a resident pursuing interventional radiology. The elective covers procedures such as thoracentesis, paracentesis, vascular access, biopsy of a superficial target lesion, and aspirating cysts/collections. Trainees also familiarize themselves with catheters, needles, and other common equipment.The final hour of the course delves into strategies for effectively communicating with patients and their families, both before procedures and in the event of unexpected complications. Raghu introduces the concept of narrative medicine; using storytelling to shift perspectives and focus on patient-centered care. By understanding the patient’s experience and acknowledging their own fallibility, students can establish a connection and provide compassionate care.

Raghu said, “The point of narrative medicine is to achieve a perspective shift through the techniques of storytelling. It allows us to focus on what we are doing to honor the patient’s experience during this vulnerable time.”

Medical practitioners can benefit the most from these narrative medicine skills during moments of emotional distress. Raghu said, “You walk in the patient’s room, sit at eye level, and talk openly about the risks of the procedure. When you speak from a place of honesty, telling them how common a procedure is and how very rare the complication is but admitting that it is possible, you gain the patient’s trust. With that trust and understanding established, even if there is an unexpected complication, it becomes easier for the patient and physician to have an open dialogue about it, process those emotions, and try again if needed.”

As part of this session, first year radiology resident Shan Sivanushanthan, MD, MS, shared a personal story of a stressful situation during his intern year and how he had difficulty sleeping after speaking to a patient’s family following a misunderstanding. The students were very grateful that Sivanushanthan shared what he learned about maintaining his focus on patient wellbeing while managing a difficult professional experience.

Raghu believes it is crucial that patient and provider wellbeing and communication are incorporated holistically into medical training using tools such as narrative medicine. She emphasized that “No matter how many times you have done a procedure or how senior you are, you are human. People won’t perceive you as weak or incompetent for having an unexpected complication despite using proper procedural techniques. Being honest and open helps everyone on your team come forward if they see a potential problem and makes it easier to troubleshoot together to help the patient. It’s not about never making a mistake once you graduate medical school; it’s about knowing how to handle the next step.”