Prostate Artery Embolization (PAE): A Physician's Perspective

Prostate artery embolization (PAE) is a minimally-invasive therapy offered at UCSF by interventional radiology physicians to patients suffering from severe symptoms of prostate enlargement, otherwise known as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). BPH is a condition that commonly affects older men. While medicines are often prescribed for BPH, some men may have intolerable side effects or persistent symptoms despite medicines. If BPH symptoms are severe enough, a patient's urologist may recommend surgical intervention.

The current surgical "gold-standard" for BPH is transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), during which a device is introduced through the penile urethra to remove prostatic tissue that is blocking the flow of urine. While many urological procedures offered to patients today are performed through the urethra, PAE uniquely treats the prostate through the arteries.

Is PAE safe and effective?

Embosphere Microspheres gained FDA-approval in the United States for PAE in July 2017, and there is a growing body of evidence supporting the use of PAE in patients with severe BPH. For background, many studies use the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) to determine the severity of symptoms, which is a scale ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 35 (most severe symptoms). In a 2016 review of 662 PAE patients, a 15-point decrease (roughly 60%) in IPSS was seen six months and one year after PAE. Another study of PAE patients found that the procedure was still effective in 76 percent of patients between three and six years after treatment.

Comparative studies with surgical procedures are limited but have been encouraging. A 2014 randomized controlled trial (RCT), demonstrated no difference in IPSS between PAE and TURP patients at two-year follow-up. Similarly, a 2016 RCT showed no difference in IPSS at one-year follow-up between TURP and PAE.

How is PAE performed?

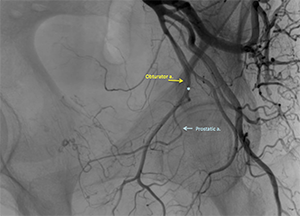

PAE is performed through a small incision in the upper thigh or wrist to gain access to your body's blood vessels (arteries). Through the access site, a soft, steerable catheter is advanced into the arteries that supply the pelvic organs. Angiography is performed, providing the interventional radiologist with a roadmap of the pelvic vessels. See Figure 1 to the left.

PAE is performed through a small incision in the upper thigh or wrist to gain access to your body's blood vessels (arteries). Through the access site, a soft, steerable catheter is advanced into the arteries that supply the pelvic organs. Angiography is performed, providing the interventional radiologist with a roadmap of the pelvic vessels. See Figure 1 to the left.

A tiny catheter is then advanced into the vessel supplying blood to the prostate. Advanced imaging techniques are then used to confirm appropriate positioning of the microcatheter. Once appropriate positioning is confirmed, small particles (microspheres) are injected through the microcatheter. The result is cessation of blood flow in the prostatic artery. As most patients have two prostatic arteries (left and right), the process is repeated on the opposite side before the catheter is removed. See Figure 2 to the left.

A tiny catheter is then advanced into the vessel supplying blood to the prostate. Advanced imaging techniques are then used to confirm appropriate positioning of the microcatheter. Once appropriate positioning is confirmed, small particles (microspheres) are injected through the microcatheter. The result is cessation of blood flow in the prostatic artery. As most patients have two prostatic arteries (left and right), the process is repeated on the opposite side before the catheter is removed. See Figure 2 to the left.

What are the benefits of PAE?

PAE can be performed on an outpatient basis with minimal sedation. Temporary symptoms such as urinary retention, rectal pain, bladder spasms, and burning/pain with urination are common for 1-2 weeks following PAE, but complications resulting in major therapy or permanent disability are exceedingly rare. Non-target embolization (mistakenly treating arteries supplying blood to organs other than the prostate) is possible but very uncommon. Another potential benefit of PAE is that it does not appear to negatively affect erectile or ejaculatory function for the average patient.

How do we determine who is a candidate for PAE?

After full urological evaluation, all established surgical options must be carefully evaluated before proceeding with PAE. For those patients determined not to be candidates for PAE, we work closely with our colleagues at the UCSF Department of Urology to find other minimally-invasive options that may be available.